In the third of our weekly series of articles by NUI Galway researchers, Dr. Louise Allcock, Lecturer in Zoology and Ryan Institute Principal Researcher in Functional and Evolutionary Biology, writes about ‘Our Marine World‘ and her work exploring Ireland’s deep sea habitats.

You don’t need me to tell you that Ireland is surrounded by sea. But do you know how deep that sea is?

Close around Ireland, on the continental shelf shown in brown on the map above, it’s not very deep – around 200 metres or so. But at the edge of the shelf, the sea floor gets suddenly deeper, dropping to around 3 km deep in the Rockall Trough, and 5 km deep on the Porcupine Abyssal Plain.

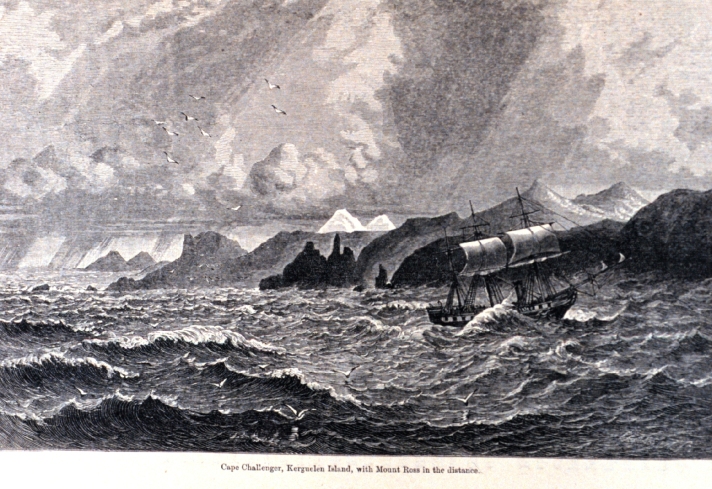

You might be surprised to learn that the deep-sea has been studied for nearly 150 years, and many of the deep-sea animals found in Ireland’s waters were first collected during the Challenger Expedition – a five-year expedition that circumnavigated the globe from 1872 to 1876. The deep-sea is surprisingly easy to sample. The sea floor tends to be flat and soft, and small trawls that work on the continental shelf will collect animals from the abyss: provided you have a long enough cable!

So is there more to learn?

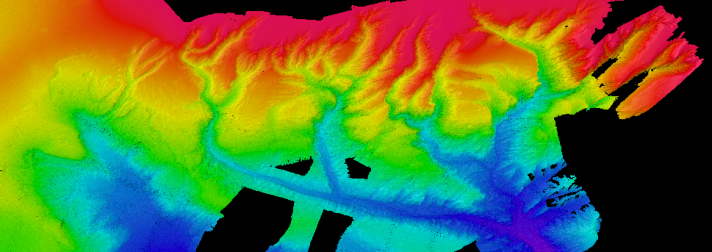

Look closely again at the real map of Ireland. Can you see canyons carving their way from the continental shelf to the deep sea? As any fisherman knows, only the foolhardy would deploy their gear here. The uneven ground will snag and rip your trawl and break your cables. So the secrets of these areas remained unknown for a long time.

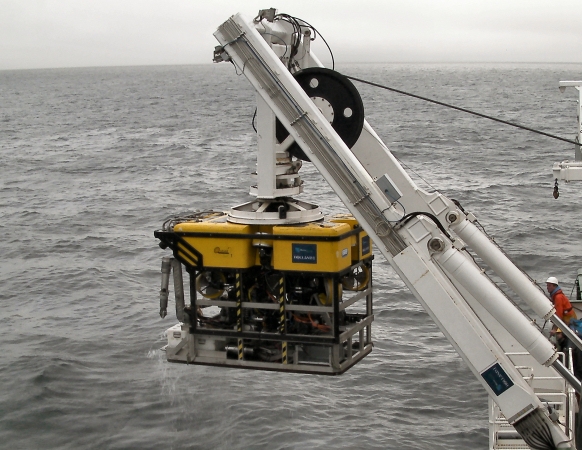

But modern technology is revealing the hidden wonders of submarine canyons. Remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) with their high definition cameras can fly up the walls of canyon systems streaming live video up fibre optic cables to the research vessel above.

At NUI Galway’s Ryan Institute, we have been using ROV Holland I, deployed from the Ireland’s largest research vessel, RV Celtic Explorer, to explore the most extensive submarine canyon system in Irish waters – the Whittard Canyon.

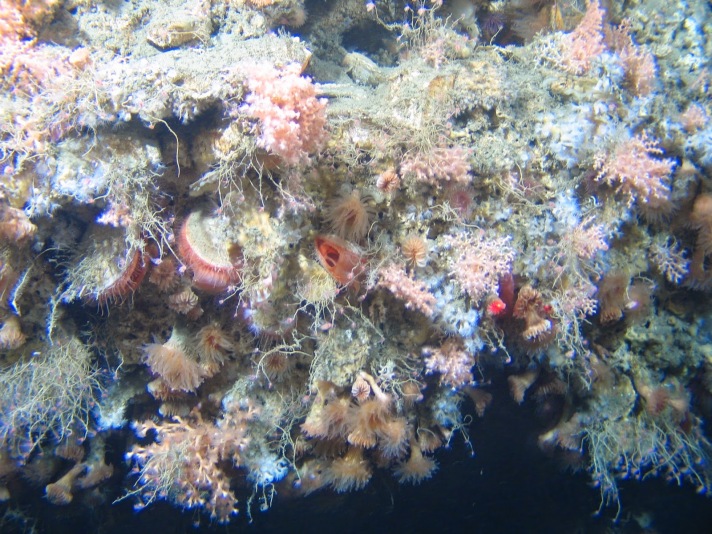

We have discovered novel habitats, such as the one shown above, which is found on vertical canyon walls between 600 and 800 m depth. We have discovered new and rare species. And we have found rich assemblages of deep-water corals.

But our research is about more than just discovery. We want to understand how these ecosystems function. The wall habitats of corals, deep-water oysters and file clams are very stable and slow growing: the oysters are thought to live to 2-300 years old. So they could take a long time to recover from any damage: be that from lost trawl gear, climate change or something else.

To know how best to protect them, we need to know which characteristics of the ocean and canyon system lead them to be there in the first place. Are the currents through the canyon delivering food? Can they just survive anywhere? To try to answer some of these questions, NUI Galway oceanographers have been studying currents and the flow of suspended particles (food for the filter feeders) through the canyon.

Deeper parts of Whittard Canyon (around 1800 m deep) are exceptionally rich and diverse in coral. There are many stony corals (similar to those that make up coral reefs in the tropics but adapted to colder waters). But more spectacularly there are lots of black corals and octocorals. These corals are soft and perhaps not at all how you might think ‘coral’ looks.

There are worldwide efforts at the moment to describe the many species, and to work out how far each species extends geographically. This is very important for conservation, because if we don’t know that an area has unique species, we cannot make such a strong case for conservation measures for that area, and nor can we ensure that all species occur in at least some protected areas.

Sometimes we need actual samples for our research and we use the robotic arms of the ROV to collect these. Using an ROV is a very environmentally friendly way to conduct research. For species we know, a photograph is sufficient, and for groups that we know need a lot of research, we can take the smallest sample possible: just the tip of a coral branch, which ensures that we have enough to extract DNA for genetic studies and to put under the microscope for morphological studies, but which leaves the coral alive and growing.

Much of our research, including, for example, genetic studies, is carried out in our laboratories in NUI Galway during the 11 months of the year when we are not at sea. But it is undoubtedly the experience of being at sea which is the highlight of the year for many marine scientists, including the NUI Galway undergraduate students studying Marine Science who join our expeditions.

You can watch some of our video (including underwater footage) from the most recent cruise:

To find out more about the 2014 expedition when we tweeted live pictures, you can read the Storify here:

https://storify.com/LouiseAllcock/celtic-explorer-cruise-ce14009-to-the-whittard-can